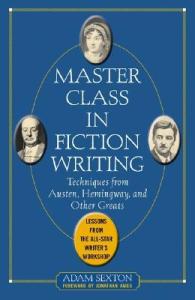

This week’s assignment for the fiction writing workshop I’m enrolled in was to write in the style of one of our favorite authors. I chose to “attempt” to write in the style of historical fiction author Philippa Gregory. In emulating Gregory, I struggled with trying to make it sound like the voice of my character, but also incorporating my own style, plus, using elements Gregory makes use of. The  problem with this is, everything the professor said not to do, Gregory does, and does it flawlessly. I took particular note of her long, compound sentences, which she often uses semicolons with. For me, the semicolon has some kind of stigma attached to it. Some people are afraid of semicolons. I’m one of them.

problem with this is, everything the professor said not to do, Gregory does, and does it flawlessly. I took particular note of her long, compound sentences, which she often uses semicolons with. For me, the semicolon has some kind of stigma attached to it. Some people are afraid of semicolons. I’m one of them.

The use of compound sentences also goes against the grain of what I’ve been trying to do with all of my stories this term. The professor advised us early in the term to keep sentences around ten words long, and I’ve been consciously making an effort to vary my sentence lengths. Gregory doesn’t use a lot of short sentences, so I felt like I was regressing to my long-winded, rambling sentences I used to write before this term. Gregory also uses a ton of adverbs, which I’ve been trying to limit in my writing. I also keep Stephen King’s writerly advice in mind about adverbs not being a writer’s friend. I tried to use some adverbs in this week’s story, but it felt like I’m telling the reader, instead of showing. Another thing that goes against the grain that Gregory does is, she deviates from the he/she said/asked dialogue tags that the professor told us to stick use. Gregory uses those simple tags, but more often she uses tags such as “she hissed” or “he added.” In a lot cases, Gregory uses adverbs with basic dialogue tags. For example, “she said bossily” or “I said brokenly.”

It’s an odd feeling trying to emulate another author’s style. It didn’t feel like me, and I felt like my writing was being held hostage because I was more conscious of trying to emulate her style. I couldn’t get my story to flow out of my brain and onto the paper. I kept teetering back and forth whether it was best to write the story first, then go back and emulate Gregory, or if it was best to incorporate her style into my story as I was writing. In the end, I’m happy with my finished story. My finished product came out more like my style but with a few stylistic elements I don’t typically use. The professor will probably take points off for my long-winded sentences that I used with semicolons. She won’t like how I deviated from the basic dialogue tags either. But I followed the assignment guidelines and wrote in the style of an author I love. I’m anxious to get my grade for this story!

I kept teetering back and forth whether it was best to write the story first, then go back and emulate Gregory, or if it was best to incorporate her style into my story as I was writing. In the end, I’m happy with my finished story. My finished product came out more like my style but with a few stylistic elements I don’t typically use. The professor will probably take points off for my long-winded sentences that I used with semicolons. She won’t like how I deviated from the basic dialogue tags either. But I followed the assignment guidelines and wrote in the style of an author I love. I’m anxious to get my grade for this story!